San Bernardino Assembly race could define what it means to be an Inland Empire Democrat

What happens when a Democratic lawmaker strays from party leaders on a key piece of Gov. Jerry Brown’s policy agenda? One assemblywoman who held back support for a sweeping climate-change bill last year is starting to find out.

Assemblywoman Cheryl Brown (D-San Bernardino) was among a group of business-aligned Democrats who objected to a provision in the bill, SB 350, that would have cut California’s motor vehicle petroleum use in half by 2030.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

March 13, 11:40 a.m.: An earlier version of this post identified Brown as a representative. She is an assemblywoman.

------------

Now Brown, a moderate, is facing what could be a bruising reelection fight against an intraparty challenger from the left, attorney Eloise Gomez Reyes. The race raises a question: What does it mean to be a Democrat in San Bernardino, where concerns over jobs often compete with those about the environment?

Some early signs indicate Brown could be in trouble. Protesters have shown up at her local events. Some of her supporters have defected, endorsing Reyes early in the fight.

“Do you ever feel that something is not going quite right?” Brown said in a recent phone interview. “They are after me, and I still don’t know why. I don’t know who ‘they’ are. But I will find out soon.”

Last week, Brown’s suspicions began to crystallize when a dozen students in breathing masks from San Bernardino Valley College threw themselves on the floor of a town hall meeting she hosted.

Brown was there to discuss the region’s logistics industry and its vast network of trucking and distribution centers, which deliver everything from headphones to heads of lettuce to big-box retailers and Amazon customers throughout Southern California.

At the event, Brown supporter John Husing, an economist with the Inland Empire Economic Partnership, discussed SB 350‘s scrapped petroleum provision, which was removed after Brown and other Democrats objected to its inclusion. Husing came to Brown’s aid, arguing that lower-income families might have been harmed by potential rising energy costs that may have resulted from implementation of the provision.

“That’s fine if you live in San Francisco and can afford a Tesla,” said Husing. “It’s not fine if you’re a poor family living in downtown San Bernardino … and the folks that stopped that deserve a welcome thanks.”

A group of twenty-somethings interrupted him, calling Brown “a corporate hack.” They held up signs that read “People over Profits” and “Don’t Sell Us Out.”

They are after me, and I still don’t know why. I don’t know who ‘they’ are. But I will find out soon.

— Assemblywoman Cheryl Brown (D-San Bernardino) on her race for reelection

But as the business community comes to Brown’s defense, a handful of local unions that endorsed Brown in 2014 have thrown their weight behind Reyes, including the Central Labor Council of the AFL-CIO of Riverside-San Bernardino, which represents more than 289,000 workers in the Inland Empire. An online campaign has highlighted the thousands of dollars Brown has accepted from oil companies.

Two Democratic state senators have endorsed Reyes. But nearly three months after asking state Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León for his support, Brown has yet to receive a response.

Though Reyes has not held political office, she’s no novice: She ran against Rep. Pete Aguilar (D-Redlands) for an open congressional seat in 2014. Though she came in fourth in that primary, she received more votes in Brown’s district — where more than 50% of registered voters are Latino — than any other candidate, according to an analysis by the California Target Book.

Reyes has proved to be an able fundraiser, bringing in $123,638 in the last six weeks of the year after entering the race in mid-November. She had nearly all of it banked at the end of 2015, while Brown raised $126,416 during the last quarter, with $156,644 cash on hand.

So far, Reyes has raised money mostly from individual donors, including a large chunk from family members, and some from unions and local businesses. Her campaign could benefit if the unions and environmental organizations that have endorsed her decide to open their deep pockets.

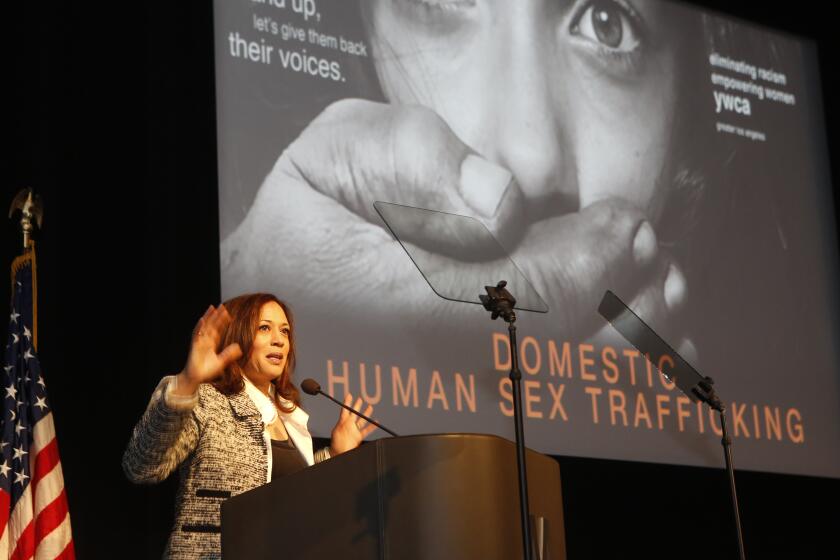

In Sacramento, where incumbents are fiercely guarded, the Democratic establishment has largely rallied around Brown, who has received endorsements from Aguilar, state Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris and a laundry list of Assembly Democrats.

But Brown is no stranger to how California’s “jungle primary” — which allows the top two primary finishers to advance regardless of party — can change fortunes in a hurry.

The surprise victory of Assemblywoman Patty Lopez (D-San Fernando) over a Democratic incumbent two years ago has become a cautionary tale, and in 2012, Brown herself beat seasoned politico Joe Baca Jr., who had the backing of the state party and strong labor support. Brown scored a come-from-behind victory after a second-place showing in the primary.

For her part, Reyes says she offers voters an alternative who “puts the interests of the community first.”

“There is a difference between Cheryl Brown and myself, and the future I see for my district,” Reyes said. “I want a safer environment, I want a cleaner environment, I want protections for our workers.”

The air over San Bernardino County often has the highest ozone levels in the region, due mostly to winds that sweep in pollution from Los Angeles. The region’s truck-to-warehouse pipeline hasn’t helped, either.

“The people of San Bernardino want clean air quality, and we do want jobs,” said Jason Martinez, 21, one of the student demonstrators at Brown’s event. “”But we don’t want low-wage jobs, warehouse jobs.”

Labor unions that previously endorsed Brown have since renounced her actions on some issues. Key among their grievances, Brown helped block a 2013 bill aimed at penalizing employers with large shares of workers on Medi-Cal. She also voted against a 2015 bill that would have put a 90-day freeze on firing grocery store employees after ownership changes.

“When you take a look at her record as a whole, there’s not one thing that I can point to that has benefited our members,” said Joe Duffle, secretary-treasurer of UFCW Local 1167.

Brown says she has voted consistently in the interest of her constituents in the Inland Empire, where only about 20% of adults 25 or older have bachelor’s degrees and about one in five live in poverty, according to census data. Voters there have shown that they’re lukewarm on environmental issues and climate change action, according to a 2012 PPIC study.

“Those are the people that I represent, and I should be their voice,” Brown said. “For me, that’s an important issue that’s lost sometimes in that beautiful building over there.”

Several of Brown’s colleagues who attended the town hall, including both leaders of the state’s Democratic moderate caucus, rushed to her defense.

Assemblyman Jim Cooper (D-Elk Grove), who is co-chairman of the caucus, told the audience Brown is “someone that’s not just going along with what everybody says, because what’s good for San Francisco or the coastal communities may not be good for San Bernardino.”

Mary Petit, who runs a community garden nonprofit, says Brown has done a good job balancing the complex, cross-cutting issues in the region.

“[Some of her votes] may not support the people who came in here and protested, and that’s OK,” Petit said. “Other times, it may not support the people who are in here today supporting her.”

For more on California politics, follow me @cmaiduc

For more, go to latimes.com/politics.

ALSO:

For San Bernardino’s elected officials, keeping busy is one way to grieve

Gov. Brown makes budget the latest battleground on climate change

California politics updates: DeLeón wades into air quality fight

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.